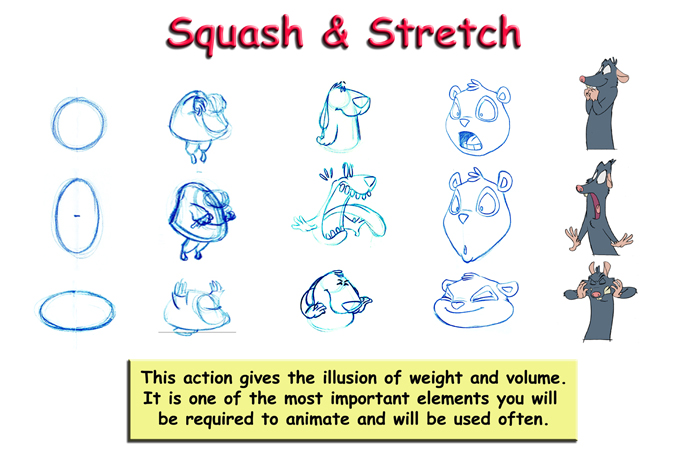

Squash and stretch is useful in animating dialogue and doing facial expressions. How extreme the use of squash and stretch is, depends on what is required in animating the scene. Usually it's broader in a short style of picture and subtler in a feature. It is used in all forms of character animation from a bouncing ball to the body weight of a person walking.

Squash & Stretch - Where? When? and How Much?

Where?

So the idea here is to add weight and volume to the character. Where are some of the places we can use this principle? Let’s start at the top and work our way down a character. In the head, if we separate the head mass into two parts, we have the cranial mass and the jaw / cheeks / jowls area. By treating these as two separate parts but connected you can add some very interesting action to head turns, takes, lip sync and any other action the head can do.

If you have my Designing Cartoon Characters for Animation books, you’ll remember that I like to treat the connection point between the cranial mass and the jaw bone as though it was an elastic band rather than a hinge (which it actually is). Adding this flexibility will allow you to drag the jaw area behind the cranium using the overlapping action principle (more about this later in the “When” section).

Then next area is in the torso of your character. The torso is made up of the rib cage and the pelvic girdle, connected together by the spinal column. Using a sphere for the rib area and the pelvis with the rubber band as the spine and again using the overlapping action principle.

The mass of each of these areas must remain consistent the same as a balloon when you press on it. One part is compressed while the other parts expand but the overall volume is still the same. You can get away with some growth or shrinkage depending on how much stretch or squash you’re trying to get away with. Think of some of the extreme positions the Wolf takes on in many of the Tex Avery cartoons. They are so extreme, that there must be some exaggeration to the volumes in order for it to look right. This goes to one of my rules of drawing which is: “If it looks good, that’s all that matters.”

You can also do stretch and squash on the arms and legs of a character depending on the action required within a particular scene. The same is true for the hands and feet. That brings us to our next question of “When?”

When?

There are so many different options here depending on the action of the character and the requirements of the scene. Let’s look at some of the obvious ones.

Head

On a head turn when the character is looking in one direction and they turn to look someplace else, either up, down or the opposite side is a good place to use this. As you know, (or should know) almost every action should have an anticipation and reaction or settle. Without these principles, your action will be stiff and mechanical. The amount of anticipation and reaction depends on how big the action is and / or the type of comedic effect you want the action to have. A character picking up a pencil off a table top doesn’t really require much of an action; it’s just the arm swinging forward maybe one foot or so and then back or up. A small action like this requires a very small anticipation, just a slight back motion before moving forward.

The same is true for a head turn, adding a slight anticipation, even just one drawing in the opposite direction can add to the action. If the character has a head design that allows for the jaw to drag a bit, you can overlap the action on the jaw and let it stretch out slightly on the turn and 1st part of the recovery, then squash as the jaw mass comes back to it’s settling position then finally hang down a bit at the very end.

On a head turn, you try to arc the path of action rather than having it travel in a straight line. The best place to add the squash to the head is in the middle of the arc on a downward motion because the head will be pressing against the chest area of the character. On an upward arc, treat it more like a bouncing ball assignment with the squash on the bottom of the beginning of the movement, stretching as it comes up and over the middle of the arc, then squashing at the bottom of the end. It could then recover back up.

On a single “down and up take”, the character would have a slight anticipation up then down into the major anticipation with the squash at the bottom then stretching long into the up position with a stagger on the end or a traceback of the extreme take pose for a few frames then into a final settle pose.

A side-to-side “double take” would have the same beginning and end as the “down and up” take but would add the rapid head turn in both directions in the middle. This rapid head turn would require some major stretching in the face to give it a fluid and elastic movement. Lot’s of overlapping action as well.

In lip-sync, the action of the character’s jaw in relation to their cranial mass will dictate how much stretch and squash you’ll need. This is based on both the character design (both physical and psychological) and the delivery of the actual lines of dialogue by the voice actor. This is something we’ll be getting into in a lot more detail later in the actual Lip-sync section of this book.

Body

The amount of stretch and squash in the body of the character depends specifically on the action of the character and their body shape. Generally speaking, the thinner a character is; the less stretch and squash you’ll get out of them. On the opposite side of the spectrum, the fatter a character is; the more stretch and squash you can give them. This is simply because the tissue that is not directly connected to the bones and muscles of the character is going to move more loosely. Compare a round balloon to a long thin one that clown’s use to make animals sculptures out of. Press on the round one, you get more displacement of mass. Press on the long thin one, you’ll get the squish in the area you’re pressing on, but the displacement is spread out over a greater area. Now you can bend the long thin one but not the round one (at lest not easily), so you can get a form of squash but it’s not the same.

Let’s look at some simple actions that you can use this in.

The most common is in the character walk. The action of the walk is such that the legs produce a slight up and down movement in the pelvis (side to side and rotating as well, see the “Walk Cycle” sections of my other book: Animation: The Basic Principles for more detailed information on this stuff). As this sphere moves up and down, the spinal column acts as a form of shock absorber for the head, thus it doesn’t move quite as much. In animation though, we want to exaggerate this type of thing wherever we can. So, what we do is create an overlapping action in the spine along with a little bit of stretch and squash (or a lot, depending on what you want to do with the character).

In a run, you can get away with a bit more stretch and squash, again depending on how heavy the character is. More weight; more stretch and squash and overlapping action.

A character jumping up and down will create quite a bit of squash and stretch depending on the distance they have to jump to or fall from. Again, the greater the distance, the more you can get out of it.

In character’s legs, any stretch or squash will relate to the action and volume. In a walk, a character with fat legs will probably have more. It also depends on the length and amount of joint flexibility.

You can add a fair amount of stretch to a characters arms when needed in certain actions such as reaching for things.

The hands can squash in smacking actions like hitting another character or the top of a table, etc.

Stretch and squash can also be applied to “wipes” or “swishes”. We’ll deal with this in more detail later.

How Much?

As I mentioned earlier about anticipation, it depends on how big the action is. The bigger the action, the bigger the anticipation and then the reaction. The anticipation should rarely be bigger than the action unless it’s for comedic purposes. Use the pencil pick-up scenario. you don’t need a big anticipation for such a simple action. If the action is big, then make the anticipation big in proportion. Putting the big anticipation for a little action is purely for the gag. You would not do this over and over because it would become unfunny a second time and annoying a third. But that’s anticipation, not squash and stretch. What’s the correlation?

It’s basically the same thing. The amount of stretch and squash depends on the action related to it. A character who jumps off a chair 18” off the ground will not have the same squash action as a character who jumps off a 1 story building. You could say the speed will dictate the amount of compression. I’m sure most of you have probably seen pictures of astronauts and pilots training in a G-force simulator. The greater the speed of the simulator, the higher the G-forces become. The face of the astronaut begins to become distorted as the simulator speeds up... a form of squash.

If you put too much on, it will distort the animation, especially in a walk or run cycle. It’s all a balancing act. As was mentioned in the description paragraph, this is one of the most important elements you will be required to master and will be used often.